The medium makes the environment

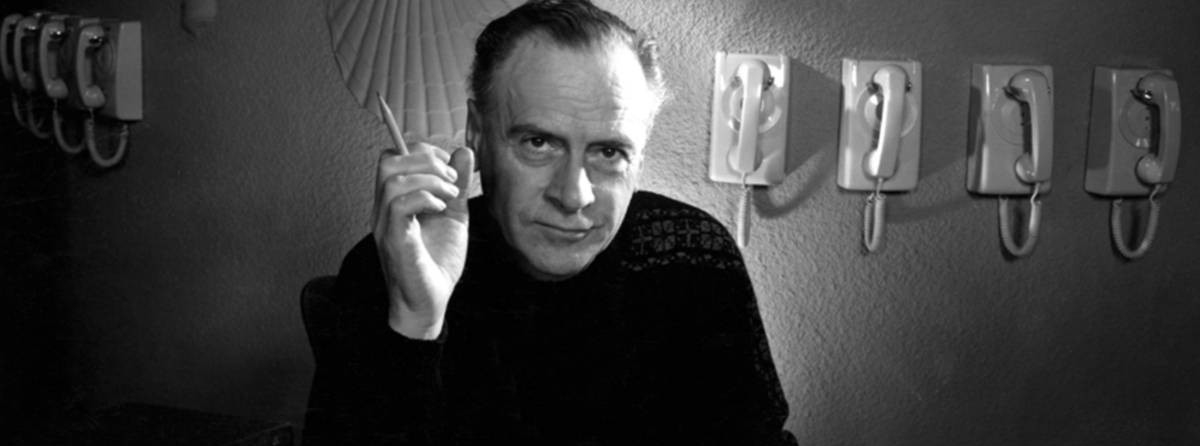

Rick DolphijnIn 1964, Canadian literary scientist Marshall McLuhan published the book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. In just a short amount of time, the book became extremely popular and McLuhan became a cult figure of sorts who could be heard frequently on the radio and television or giving presentations at home and abroad. He was a guru for the new generation, and even people like John Lennon wanted to attend his lectures.

His rise in popularity could be attributed to the fact that he was (the first) to voice well thought-out ideas about what a ‘medium’ actually was. His main claim was that not every medium was a means to communication, but that, as the subtitle of his book suggests, they were above all extensions of the human capacity to communicate. The radio ‘amplifies’ the voice and brings it into every living room, while the television has the added benefit of the moving image. But it is somewhat more complicated than that. McLuhan also states that, on the basis of this definition, a car is a medium, seeing as it does convey a message from A to B (the message is the person) and above all, functions as an extension of our human capabilities; the car allows us to move much faster than our legs could ever take us.

The car is perhaps an unusual but interesting example of a medium, as McLuhan imagines it, because we all have experienced that this medium does not ‘just’ convey a message. The car ensures that we perceive the landscape in a completely different way than if we were to travel by bicycle or on foot. When we walk, we notice the flowers and might follow winding sand or stone paths. Being in a car reveals a very different landscape, one of vast fields or even a radiant horizon. The medium does not only transport, it makes the environment. Or, in McLuhan’s terms, if we want to understand how a medium functions, we should not look at the message the medium carriers with it, but at what the medium does. Ergo, the medium is the message.

This is exactly what McLuhan wants to demonstrate: that the medium, with the element of transportation, makes the environment. In this way, according to the logic of the medium, McLuhan wants us to view the world and our (recent) past in a different way. He is not afraid to make bold statements. According to McLuhan, the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century was much more important than all of the books that have been printed by it ever since. It caused us to look at the world differently, but also ensured that the world itself increasingly behaved in accordance with the art of printing. For example, the printing press meant that legislation could be introduced and distributed much more easily, which led to the rapid growth of cities in Europe. It allowed for Bible translations to become more reliable (no longer just the work of passionate monks but of a professional translator who was instructed to make the book accessible to a larger number of people). According to McLuhan, it was because of the printing press that the monk Martin Luther was able to carefully study the Bible and, as a result, realise that the Word of God was at odds with the ways the papal rulers had interpreted them (eventually leading to the Reformation in 1517).

"In McLuhan's time, the 'electronic age', radio and TV made a new society"

Starting from his definition of the medium, McLuhan demonstrates that the medium not only depicts a landscape but gives it real meaning. The medium makes a society, a period of time even, in this case the Gutenberg era in this case. “The medium is the massage,” he therefore said, if somewhat ironically; the medium massages the people and their environment into a new society. And thus, according to McLuhan, there are different eras that can be distinguished according to the medium that was ‘dominant’ at that particularly point in time. Referring to his own time, he wanted to demonstrate how the ‘electronic era’, in which radio and TV (from the 1960s) played an increasingly dominant role, formed a new society. The second half of the 20th century was formed, according to him, by modern electronics. The creation of a ‘Global Village’ (his term) is no more than the consequence of what electronic media do: they bring everything in contact with everyone, in such a way that we can instantly know what is happening on the other side of the world but have a clue of how our neighbours are doing. Because just like the car alienates us from the flowers and dirt paths, electronic media are not capable of bringing us into contact with the world that is just outside our door.

Finnegans Wake - James Joyce (source: genius.com)

In order to understand how a medium creates a new society, McLuhan recommends looking at the ways in which the arts explore that medium. As noted, McLuhan was trained as a literary scientist, which meant that he had a great love for the work of the likes of James Joyce from an early age. He considered Finnegans Wake, Joyce’s most experimental work, one that 1,000 books enclosed in it, to be his most interesting. With this masterpiece, Joyce was able to demonstrate what a book as a medium could do. It is of course interesting to write the spoken word down, to keepsake beautiful stories for the future, and to allow people to experience a tormented protagonist, but that does not allow us to see what the book, as a medium, can actually do. McLuhan posits that Joyce was a writer who was explicitly looking at what makes a book a book. Joyce did not tell a story with a beginning and an ending, but instead tied many stories together in countless different ways (through one another and woven into one another). He did this – and this is very important – because the book (as opposed to a spoken story) allows you to do it. After all, you can read a book more carefully, you can flip back a few pages, you can put it down and pick it back up again.

The poet Stéphane Mallarmé, just before Joyce, explored what makes a poem on paper different from the one spoken out loud, and did so by incorporating the layout of the print into the poem with the use other fonts and by breaking sentences in unexpected places. Why should words always appear in the same way, in straight lines, on a piece of paper? Does the book not offer us entirely different ways of expressing ourselves, and should we not, as artists, explore that? McLuhan was interested in the work of Pablo Picasso for that same reason. He realised that painting as a medium does not limit itself to portraying a woman’s face from a single perspective. Why can I not see it in 10 different ways at the same time? The canvas allows for this does it not?

"Light has always been of the utmost importance in our visual culture."

Marshall McLuhan died in 1980 but his work is still widely read and used today to carefully analyse ‘the digital age’. How does the digital medium break from the electronic? In what way does digital culture show us a different landscape, and how does it shape it? From McLuhan’s perspective, we would have to say that ‘the digital’, as a medium, is more influential than any algorithm or protocol. And if we want to understand more about how our world is shaped by the digital, we must, with McLuhan, look at the ways in which the arts are exploring this new medium.

And with that ‘light’ suddenly becomes very interesting, if it was not already. Light has always been of the utmost importance in our visual culture. Every Dutch master, every photographer, and every filmmaker would have to admit that light reveals ‘the portrait’, but also makes the landscape. In light art today, we see that the electronic has made way for the digital. In line with our time, we see that artists are creating very different kinds of portraits and landscapes. In the city – which once served as the décor for the Dutch masters and was known as ‘Bibliopolis’ due the many publishers of the free word who had settled here and who spread their message throughout the Republic of Letters thanks to the invention of the printing press – ‘the light’ will now, digitally, reveal a ‘different city’. Let us see how these works of art explore the landscape of the digital age, how they shine a light on our society, and how different it already is from the electronic era that we have only just left behind.

Rick Dolphijn

Rick Dolphijn (NL) is a philosopher at the Department of Media and Cultural Sciences, Utrecht University. He has also been appointed Honorary Professor (until 2020) at the University of Hong Kong. He conducts research into media and culture theory, contemporary art and developments in philosophy. His latest books (selection) are New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies (w/ I. van der Tuin) and Philosophy After Nature (w/ R. Braidotti, ed.).